Teambuilding to Start the Season on the Same Foot

-

January 2026

- Jan 11, 2026 Book of the Month: Deep Work by Cal Newport Jan 11, 2026

- Jan 4, 2026 Your One Action for 2026 Jan 4, 2026

-

December 2025

- Dec 31, 2025 Top Stories of the Year Dec 31, 2025

- Dec 19, 2025 Book of the Month: Mastery by Robert Greene Dec 19, 2025

- Dec 15, 2025 Removing Popcorn Ceilings For a Cleaner Finish Dec 15, 2025

- Dec 7, 2025 Late Fall Real Estate Market Updates Dec 7, 2025

-

November 2025

- Nov 23, 2025 Book of the Month: Peak: Secrets From the New Science of Expertise by Anders Ericsson and Robert Pool Nov 23, 2025

- Nov 19, 2025 8 Home Maintenance Tasks To Check Off Your List Before Winter Nov 19, 2025

-

October 2025

- Oct 23, 2025 Book of the Month: Find Your Why by Simon Sinek Oct 23, 2025

- Oct 13, 2025 How Capital Gains May Impact Real Estate Decisions Oct 13, 2025

- Oct 2, 2025 Me Meetings to Get Priority Tasks in Order Oct 2, 2025

-

September 2025

- Sep 25, 2025 5 Soccer Teambuilders Any Coach Can Use Right Now Sep 25, 2025

- Sep 17, 2025 What to Know about a Home Appraisal Contingency Sep 17, 2025

- Sep 11, 2025 Teambuilding to Start the Season on the Same Foot Sep 11, 2025

- Sep 5, 2025 Book of the Month: The 5 Types of Wealth by Sahil Bloom Sep 5, 2025

-

August 2025

- Aug 28, 2025 Rent vs Buy: By the Numbers Aug 28, 2025

- Aug 22, 2025 Leaving Everything on the Field Aug 22, 2025

- Aug 17, 2025 Books of the Month: The Creative Act: A Way of Being by Rick Rubin and The War of Art by Steven Pressfield Aug 17, 2025

- Aug 13, 2025 Rent vs Buy: How to Choose Aug 13, 2025

- Aug 6, 2025 Inspection Contingencies and Timelines Aug 6, 2025

- Aug 3, 2025 Lessons From Painting and Soccer Camp Aug 3, 2025

-

July 2025

- Jul 23, 2025 Finding the Point Jul 23, 2025

- Jul 16, 2025 Book of the Month: Think Like a Monk: Train Your Mind for Peace and Purpose Every Day by Jay Shetty Jul 16, 2025

- Jul 9, 2025 Real Estate Market Updates: June 2025 Jul 9, 2025

- Jul 2, 2025 Taking Time Out to Re-Align Jul 2, 2025

-

June 2025

- Jun 25, 2025 Navigating Home Sale Contingencies Jun 25, 2025

- Jun 17, 2025 The Crossing Fawn Jun 17, 2025

- Jun 4, 2025 Book of the Month: Notes from a Deserter by C.W. Towarnicki Jun 4, 2025

-

May 2025

- May 29, 2025 We Are What We Eat May 29, 2025

- May 22, 2025 The Ins and Outs of Mortgage Contingencies May 22, 2025

- May 8, 2025 Coaching Fundamentals: Reflect and Repeat May 8, 2025

-

April 2025

- Apr 23, 2025 How Rory McIlroy Remained Present to Win the Masters Apr 23, 2025

- Apr 2, 2025 Coaching Fundamentals: Mastering the Demonstration for Player Understanding Apr 2, 2025

-

March 2025

- Mar 12, 2025 Book of the Month: Atomic Habits by James Clear Mar 12, 2025

-

February 2025

- Feb 27, 2025 5 Answers For Potential Homebuyers Entering the Spring Market Feb 27, 2025

- Feb 6, 2025 Investing Basics with Chris Strivieri, Founder and Senior Partner of Intuitive Planning Group in Alliance with Equitable Advisors Feb 6, 2025

-

January 2025

- Jan 30, 2025 Book of the Month: The MetaShred Diet Jan 30, 2025

- Jan 20, 2025 Residential Housing Trends in 2025 Jan 20, 2025

- Jan 9, 2025 Understanding the Use and Occupancy Certificate Jan 9, 2025

-

December 2024

- Dec 4, 2024 Book of the Month: How Champions Think by Dr. Bob Rotella Dec 4, 2024

-

November 2024

- Nov 19, 2024 Professional Spotlight: Fran Weiss, Owner of Weiss Landscaping Nov 19, 2024

-

October 2024

- Oct 29, 2024 Book of the Month: Hidden Potential by Adam Grant Oct 29, 2024

- Oct 21, 2024 Professional Spotlight: James George, President, Global Mortgage Oct 21, 2024

- Oct 15, 2024 Buyers Post-NAR Settlement Oct 15, 2024

“A player who makes a team great is more valuable than a great player.”

--John Wooden

For decades, coaches have been improving player development by attaining and transferring knowledge on technical, tactical, and physical skills and concepts. However, in most team environments, social and emotional development is still often overlooked. A coach can have a great collective of individual players, but if the team doesn’t work cohesively toward a common goal, it will get no further than a group of less talented individuals. In today’s push to accelerate players to the highest levels, we’re missing out on the social and emotional progressions, especially on the heels of a pandemic that continues to affect some children (and adults) years later. And when young players cycle through teams like a revolving door, at some point the lack of social and emotional development will catch up when their skills begin to plateau.

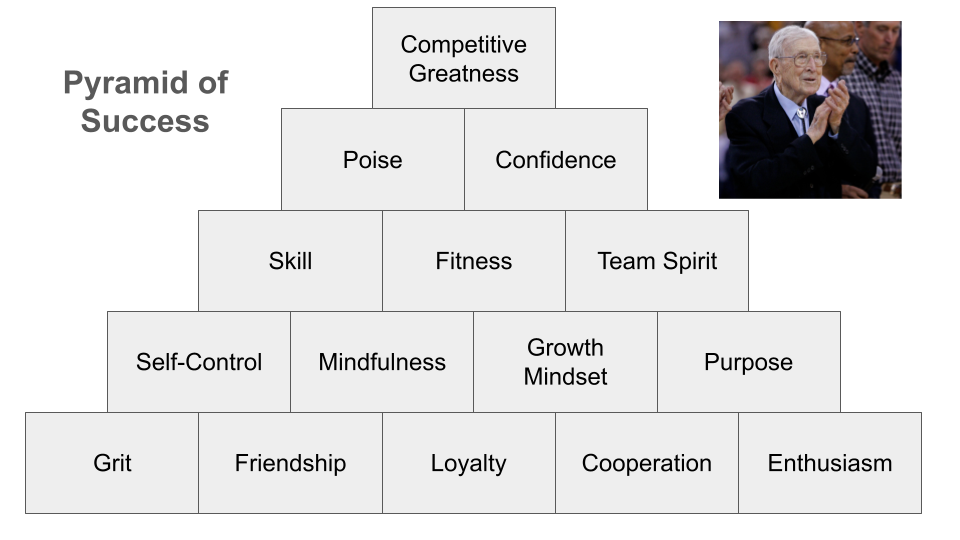

For as long as I’ve been teaching and coaching, I’ve turned to John Wooden’s Pyramid of Success. Wooden, the longtime basketball coach at UCLA in the 1940s through 1970s, wasn’t the first coach to emphasize team culture or social development. But he certainly found a model that matched his own values. From 1967-1973, Wooden’s teams won 7 of their 10 NCAA titles, back when a team had to win the conference to get to the NCAA tournament. Even with NBA legends Lew Alcindor (Kareem Abdul-Jabbar) and Bill Walton, Wooden’s teams exemplified teamwork both on and off the court.

What made Wooden’s methods unique was that his goal was never to win. His goal was what he perceived to be Competitive Greatness, or playing the best a team could play. Contrary to the modern era, where many attempt to prioritize product over process, Wooden was a strong proponent of the idea that winning is a potential benefit of performance. Teams can play great and lose or play poor and win, so controlling the process and performance became his team’s mission.

Building a cohesive team is an entirely different coaching skillset, but devoting early parts of the season to teach essential team skills can lead to elevated performances down the line. If a team thrives early, coaches can reinforce team skills that are firmly in place, while a drop in performance could result in identifying specific team skills to practice in future training sessions. Once a foundation is set, a team moves closer to reaching Competitive Greatness.

Some terms have been revised

Expecting players to naturally improve how they interact is like expecting every back heel to end up in the back of the net. Children and young teens (even adults) benefit from learning how social and emotional components influence the team’s performance in positive and negative ways. If the goal is to build the best team then practicing how to function as a team and how to respond to expected team situations becomes just as important as teaching technical, tactical, and physical skills.

How do we teach team skills?

Spencer Kagan, a longtime educator and proponent for cooperative learning, uses the acronym PIES when determining if an activity enhances cooperative learning. Kagan believes there’s a difference between a team activity and one that builds cooperation.

PIES stands for:

P- Positive Interdependence

I- Individual Accountability

E- Equal Participation

S- Simultaneous Interaction

Positive interdependence encompasses the relationship teammates share when relying on each other to reach common goals. Individual accountability holds every team member responsible and eliminates the person in the group who watches everyone else do the work. This is different than star players getting more action. In some ways, individual accountability also involves managing players, especially when one player’s mistakes are blips but that same player highlights others’ mistakes as if they were apocalyptic.

Every player has a role or function in a team. Some roles look and feel different than others. Equal participation in a cooperative sense ensures every player contributes. Whether it’s to score goals or prevent them, ever player should know their role and be actively fulfilling those roles at the same time. One of the hardest jobs for a coach is maintaining the motivation and preparation of players not in the game. However, whether coaching six year-olds or sixteen year-olds, the last player on the depth chart should feel as important as the first.

When teaching team skills, I’ve blended cooperative adventure learning models with competitive environments that relate more directly to the what our teams will experience together. Though many educators try to separate cooperation and competition, I believe they can be taught together. If we want our teams to function as a cooperative unit, players need to be mindful of the impact from single-minded winning, which can lead to cheating, implosions, stunted development, or even the loss of satisfaction associated with a strong performance because of a poor result. Instead, we want the satisfaction of winning to come from the positive social and emotional environment when a team, not just certain individuals, collaborates equally toward a common goal.

Players learn from the culture coaches create.

(Coming Soon: 5 Soccer Teambuilders Coaches Can Use Right Now)